Increscunt animi, virescit volnere virtus.

“The spirits increase, vigor grows through a wound.”

-Aulus Gellius, 2nd C., quoted by Friedrich Nietzsche in Twilight of the Idols

Twilight

Bitforms

May 7 – June 6, 2009

Featuring a transfixing display of sculpture and animated video installations, Twilight is an exhibit that uses the language of Rococo painting and the tenebrism of film noir and gothic fiction to develop a cyber-feminist narrative inside the space of a 3-D gaming world. Depicting forces of life by using a graphical language, Hart treats the figure as a virtual avatar that hovers in a cycle of decay and transformation. Hart embraces the Nietzschean concept that death and decadence are an intrinsic part of the cycle of growth.

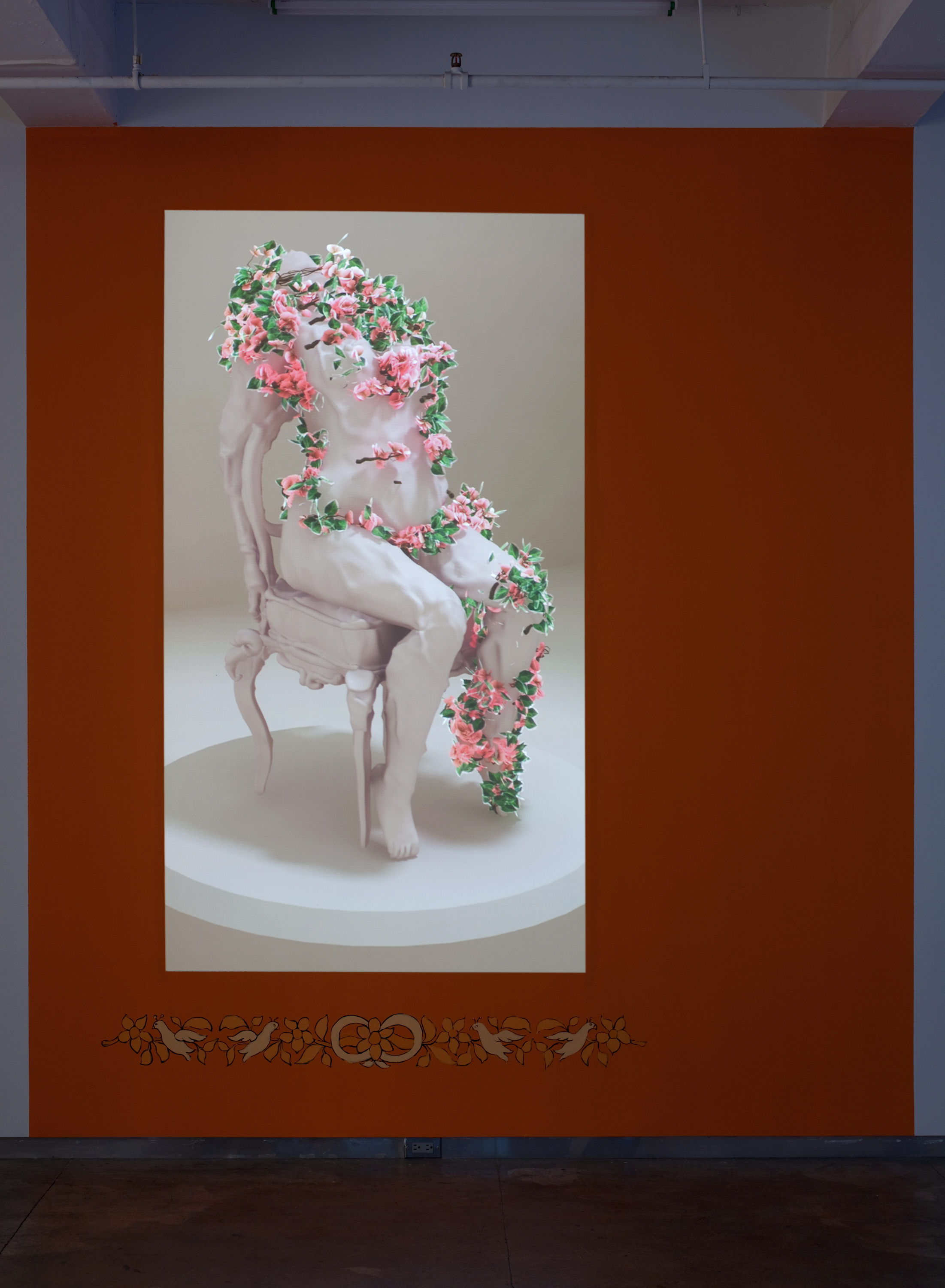

Set to a mix of crumpling paper, “The Seasons” (2009) portrays a white on white room in which a slowly evolving sculptural figure gradually transforms. In this work, a seated woman in a pose of erotic abandon cycles clockwise on a rotating pedestal. As she cycles, she decomposes, a vine of roses surrounding her- blooming and then fading away. Bringing to mind the buttery visual language of a wedding cake decoration, the animation is set within a sterile room revolving counter-clockwise, as a camera pans back and forth. These movements function in counterpoint, appearing only at the edge of our perception. All is in flux but time seems to stand still, as in life.

Inspired by the visionary architectural languages of Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, Étienne-Louis Boullée and Jean-Jacques Leque, Hart’s work is informed by the histories of art and architecture. Hart uses animated techniques to create sublime landscape gardens often containing expressive and sensual female bodies that interject emotional subjectivity into what is typically the over-determined Cartesian world of digital design. Decorative yet dark, the pieces she creates exist somewhere in the psychological realm of Edgar Allen Poe, H.P. Lovecraft, and contemporary procedural crime dramas.

“The Swing” (2006) features a plump nude avatar, named Machina, whose appearance is loosely based on Baroque painter Peter Paul Reuben’s portraits of his wife, and personifies Rococo fleshy decadence. In this multi-channel animated installation, the character swings on a seat suspended from the sky, set inside super Mannerist slow time. Her wooded surroundings ebb and flow at another rate, imitating stop-motion, as years pass in a matter of moments. The driver of all of these cycles, but a driver scarcely in control, this female figure is a Mother Nature heading straight for what she suspects might be Oblivion.

Hart’s “Mortification” series relates figurative form to corrosive printmaking techniques and etched surface textures that evoke cross-hatch drawing. These works, such as “Grand Mortification” (2008), feature a realistic, computer model of a nude that is digitally “mutilated” and subjected to irregular, apparently organic, deformations. By juxtaposing natural form that evokes rot and decay with a material - ABS plastic - that is typically associated with industrial manufacturing, the “Mortification” works propose a digital Baroque. In keeping with the historical definition of Baroque, the emotionally expressive and personal style of this sculptural imagery also breathes irregularity and livelihood into the oppressive anonymity of technological culture. Appearing painstakingly carved and shaped in gesture, this series of work is physically output from a rapid prototype machine using virtual 3-D models.

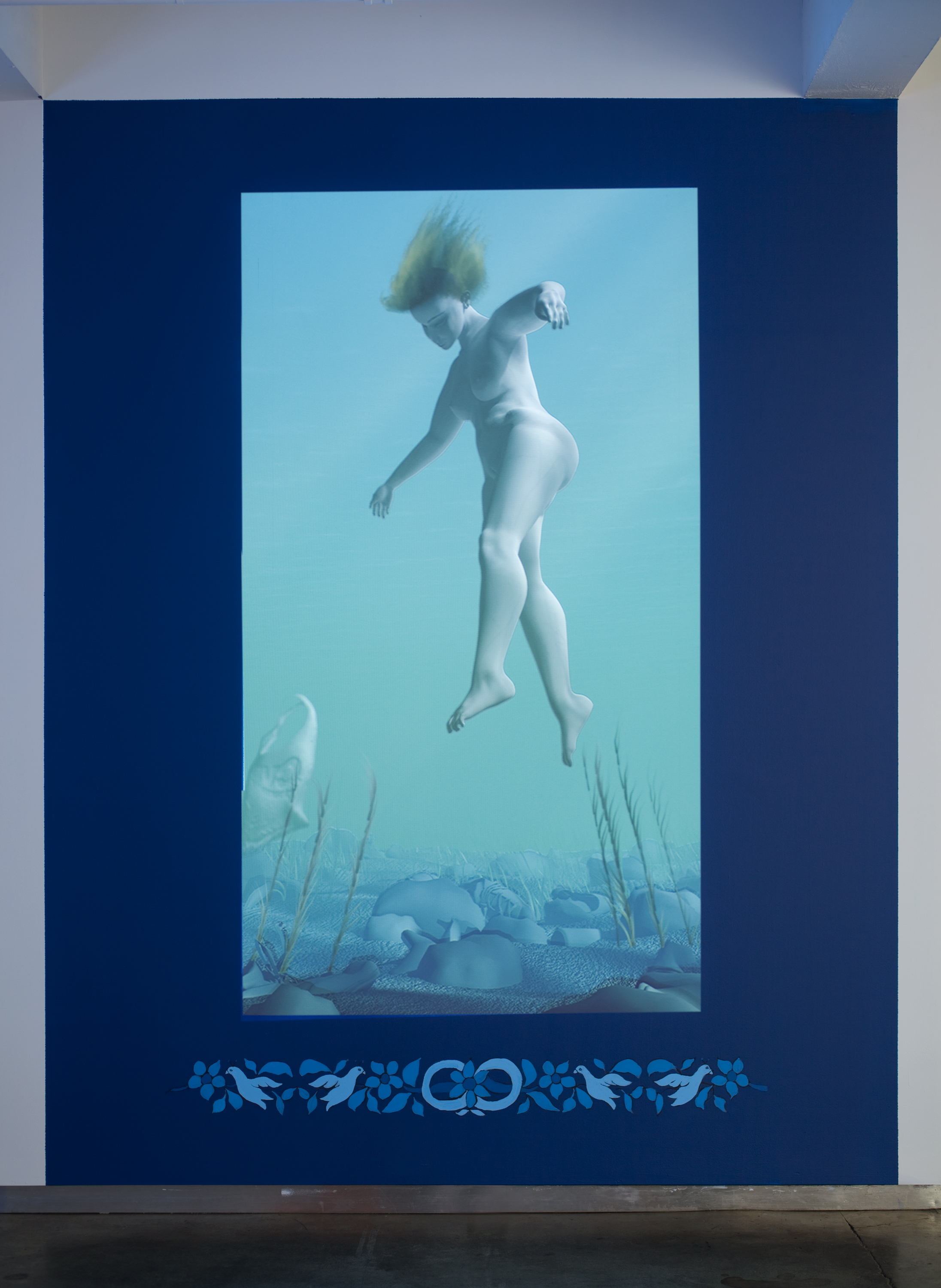

A screen-based animation, “Ophelia” (2008) sets the body of a naked woman adrift at the bottom of the ocean. Ophelia floats at the bottom of a sea littered with refuse and drifting fragments of plastic bags. Although visually, these plastic bags are seductive, reflecting light softly, they are nevertheless Pelagic plastics, non-biodegradable, now littering our oceans to a life-threatening degree. Fish eat six times more Pelagic plastic fragments than plankton, and the hormone disruption to fish and birds, and now to our own food chain, by this has not yet been measured. Ophelia is therefore an ode to loss, not just of youth and love as in Hamlet, but also to our own natural world and the possibility of living harmoniously within it.

Evoked by the dreamy atmosphere of an underwater environment, this figure is caught in an ambiguous state of death or sleep. Although the advanced techniques of dynamic particle and optical simulation have been used to produce this imagery, Ophelia is nevertheless a tragic and a romantically erotic figure. Hamlet’s lover, Ophelia has been written about by literary critics as a feminist figure embodying the Electra complex, a mad woman who drowned herself for love of a man who murdered her father. In the archetypal Pre-Raphaelite painting Ophelia (1852), John Everett Millais created a “dense and elaborate pictorial surfaces based on the integration of naturalistic elements…described as a kind of pictorial eco-system.” This reference however reveals another layer of tragedy in this contemporary 3-D Ophelia. Hers is the tragic collision of the scientific and the natural worlds embodied by the advanced technology used to produce it and this particular image.