Ouutlnds!#? Ouutlnds!#? Ouutlnds!#? Ouutlnds!#?

Ouutlnds!#?

A New Alchemy

Claudia Hart

June 28, 2024

An artist reflects on Bitcoin’s status as digital gold and a substrate for her work.

On January 10, 2024, the US securities regulator approved the first US-listed exchange traded funds (ETFs) to track bitcoin. The next day, 4.6 billion USD worth of ETFs were exchanged—a watershed moment for the cryptocurrency industry. I viewed these enactments as a kind of ritual performance, endowing Bitcoin with the aura already inherited by the US dollar when the gold standard was broken in 1971.

In February, not long after Wall Street listed its first Bitcoin ETF, I was invited to participate in the first Sotheby’s auction of Ordinals—digital assets that are like NFTs, but to me far more interesting. After those first trades, Ordinals by proxy had the mythological status of gold.

In February, not long after Wall Street listed its first Bitcoin ETF, I was invited to participate in the first Sotheby’s auction of Ordinals—digital assets that are like NFTs, but to me far more interesting. After those first trades, Ordinals by proxy had the mythological status of gold.

Of course, Bitcoin had been known as “digital gold” for some time. On September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, triggering an international banking crisis. On October 31, 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto published the Bitcoin whitepaper, which literally equated the cryptocurrency to gold, and named the encryption process “mining”: “The steady addition of a constant amount of new coins is analogous to gold miners expending resources to add gold to circulation. In our case, it is CPU time and electricity that is expended.”

The aura of Bitcoin was now newly enhanced by its stock-market listing.

To better understand the implications, I contacted Rhea Myers, whose knowledge of cryptocurrencies is profound. She gave me a reading list of histories of digital currencies that were published in 2022–23, as Bitcoin was ascending in the global financial market. These books chart finance, science, business, and digital art. They are also cosmological narratives that express symbolic structural relationships and universal orders, where utopia’s glow emanates from just over the horizon. I spent the next month reading these books. This essay is a story of these stories: how mythmaking made a technology seem inevitable

In Norse mythology, Idun is the goddess of youth. She has a basket of golden apples that keep the other gods young—until the end of the world.

In Norse mythology, Idun is the goddess of youth. She has a basket of golden apples that keep the other gods young—until the end of the world.

In the open-world sandbox game Minecraft (2011), golden apples bestow special effects on players, keeping them alive longer, and heal zombie villagers.

Extropianists were adherents to a cult of the golden apple, in pursuit of immortality. They were an on- and offline group of Bay Area technologists instrumental in developing the coding language and culture that envisioned, designed, and finally encoded Bitcoin. Among those who attended meetups between 1994 and 2005 was Mike Perry, overseer of seventeen frozen heads and ten frozen bodies submerged in liquid nitrogen at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona. In a 1994 Wired interview, Perry predicted a future in which people will download their mind into a computer and make backup copies that lasts forever. “Immortality is mathematical, not mystical,” he said.

Extropianists were adherents to a cult of the golden apple, in pursuit of immortality. They were an on- and offline group of Bay Area technologists instrumental in developing the coding language and culture that envisioned, designed, and finally encoded Bitcoin. Among those who attended meetups between 1994 and 2005 was Mike Perry, overseer of seventeen frozen heads and ten frozen bodies submerged in liquid nitrogen at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona. In a 1994 Wired interview, Perry predicted a future in which people will download their mind into a computer and make backup copies that lasts forever. “Immortality is mathematical, not mystical,” he said.

The Extropians aimed to build a society based on self-generating systems of order, in resistance to the legal structures imposed by a federal state.

In ancient Egypt, pharaohs were mummified by wrapping the body in cotton and draping it with amulets. A properly prepared mummy bridged the spirits of the deceased and the offerings from the living. Until Extropianism, the Egyptians were the only culture to have held the preservation of the corpse as a specific religious belief. But there is still a significant difference between the two. The ancient Egyptians believed that the heart, rather than the brain, was the organ of reasoning. It was therefore left in place within the body and, if accidentally removed, was immediately sewn back in.

Death and decay are forms of entropy. Extropianism extolled entropy’s opposite—eternal life, the transhuman or the posthuman. Extropianists prided themselves for being supermen with augmented intellects, memories, and physical powers. Their goal was to build a society based on self-generating systems of order, in resistance to the legal structures imposed by a federal state. To finance it, they defined an anonymous digital currency that functioned outside the physical gold standard, yet garnered its mythologies. Some believe that Satoshi Nakamoto is the pseudonym of Nick Szabo, an Extropian. But even if that’s not the case, the connection between Nakamoto’s ideas and the Extropians’ is clear: both wanted to transcend the structures governing human life.

The proof of work protocol is what enables Bitcoin. One party proves to others, who serve as verifiers, that a certain amount of computational effort has been expended. The system requires miners to compete with each other to be the first to solve arbitrary mathematical puzzles. The winner of this race gets to add the newest batch of data to the blockchain. The winners receive their reward in Bitcoin, but only after other participants in the network verify that the data being added to the chain is correct and valid. As a result, Bitcoin and the other cryptocurrencies do not have centralized gatekeepers. Instead, they rely on a distributed network of participants to validate incoming transactions, adding them as new blocks to the chain.

Proof of work is necessarily relational, performed by a chain gang of players and effective because of that. It can therefore also be thought of as a performative ritual of enactment, as the parties go through the requisite set of actions to affirm value. This makes digital gold conceptually very different from physical gold and the financial standards based on it. It is a process of pure computation enacted by people and machines, together expending massive amounts of energy and heat. In doing so it produces a Marxian metaphor of work: heat driven by time, transformed into a monetary unit.

Proof of work can be thought of as a performative ritual of enactment.

My artistic motivation is to extend the arrow of art history, rather than break from it. When I started working with 3D animation and simulation technologies in the late ’90s, I was still a painter living in New York.

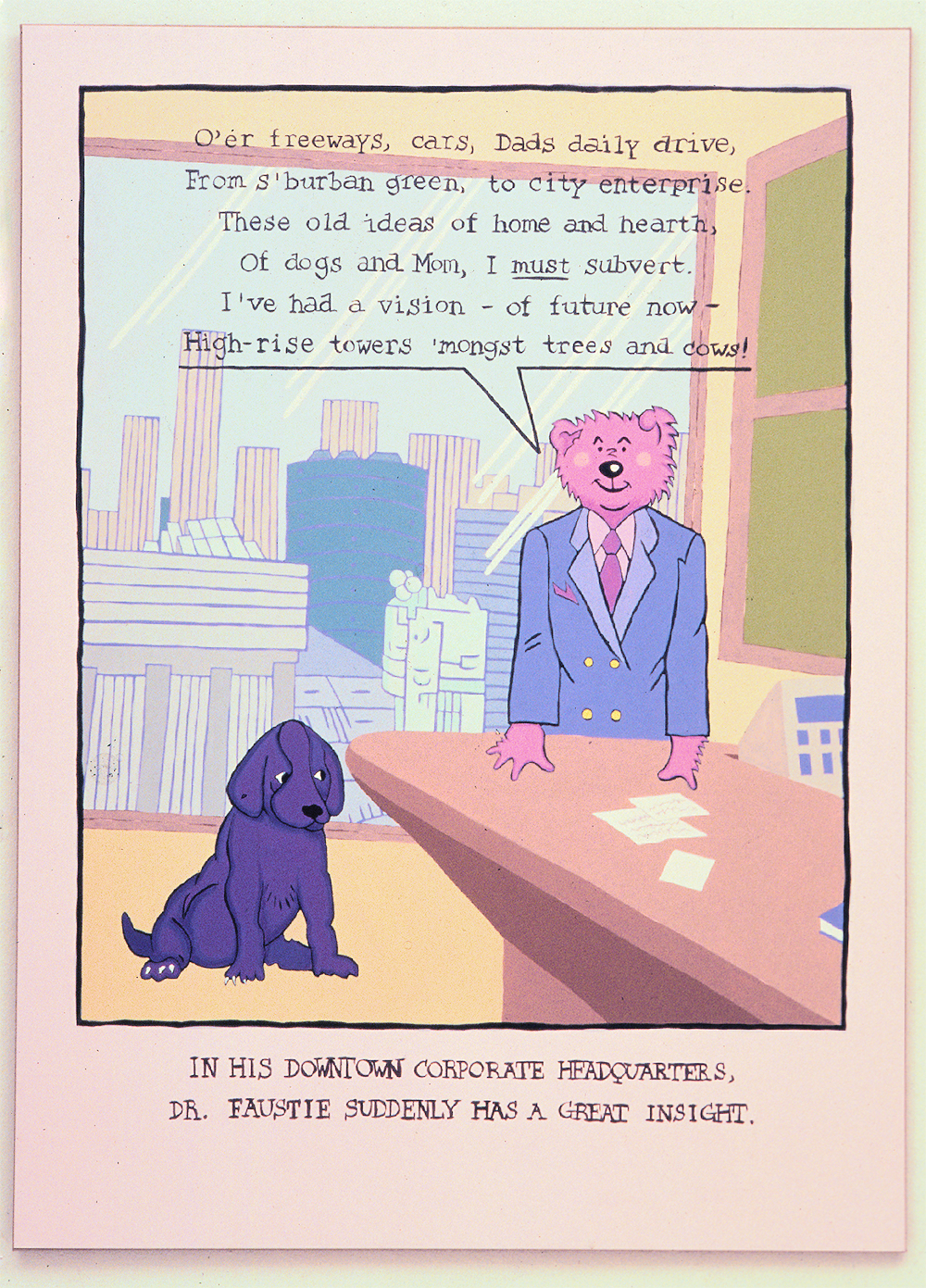

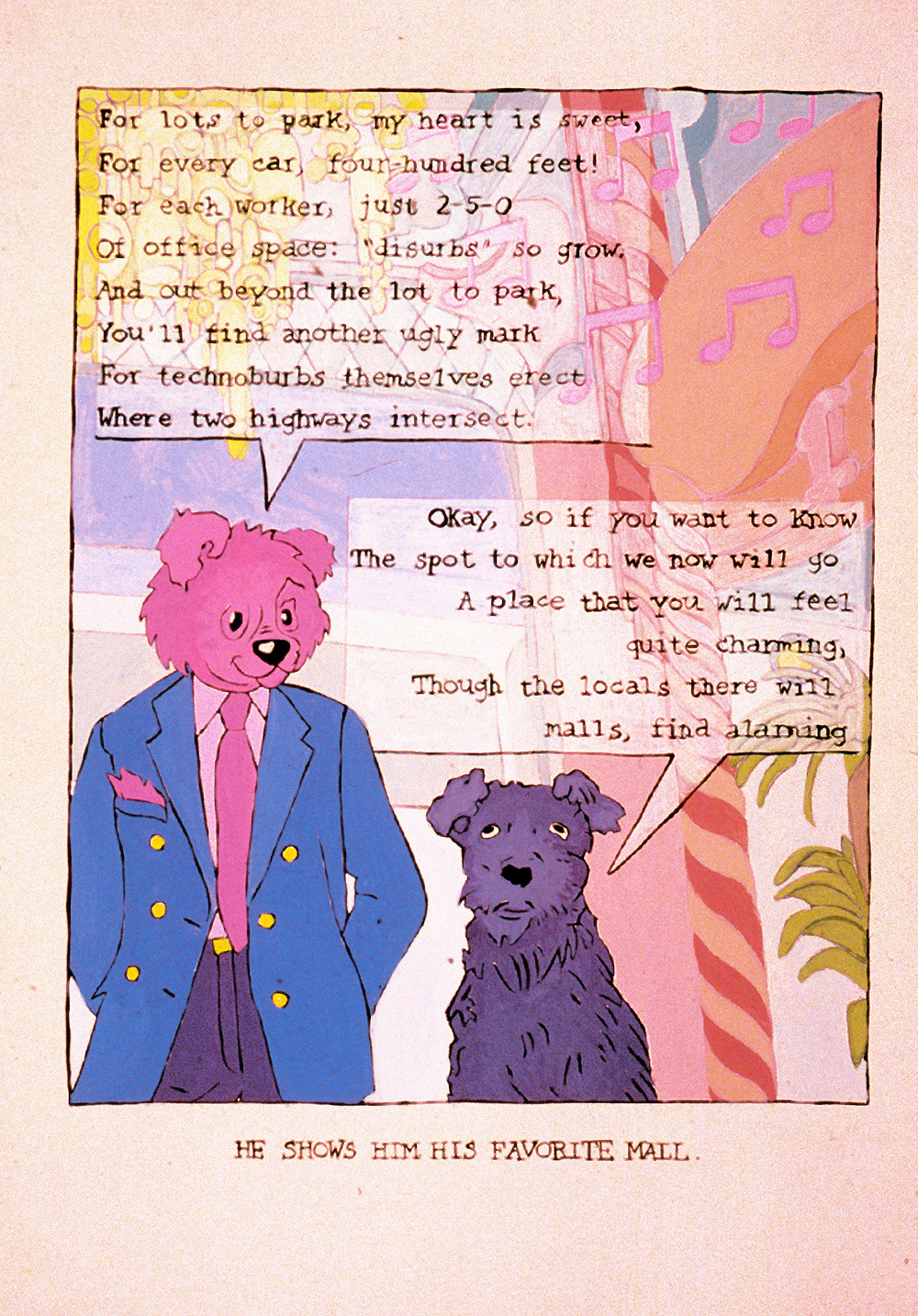

I started writing illustrated books in an era before the term “graphic novel” was coined. We had comix, a punk, political version of the mass comic-book form, meaning a thing not accepted as art (and mostly still not). I was a fan of Art Spiegelman’s cerebral comix Maus (serialized from 1980 to 1991). I was inspired by Spiegelman to produce two fake children’s books based on adult themes of power and its abuse: A Child’s Machiavelli (Realismus Studio,1995) and Dr. Faustie’s Guide to Real Estate Development (Nautilus, 1996), a reinterpretation of Goethe’s Faust.

I started writing illustrated books in an era before the term “graphic novel” was coined. We had comix, a punk, political version of the mass comic-book form, meaning a thing not accepted as art (and mostly still not). I was a fan of Art Spiegelman’s cerebral comix Maus (serialized from 1980 to 1991). I was inspired by Spiegelman to produce two fake children’s books based on adult themes of power and its abuse: A Child’s Machiavelli (Realismus Studio,1995) and Dr. Faustie’s Guide to Real Estate Development (Nautilus, 1996), a reinterpretation of Goethe’s Faust.

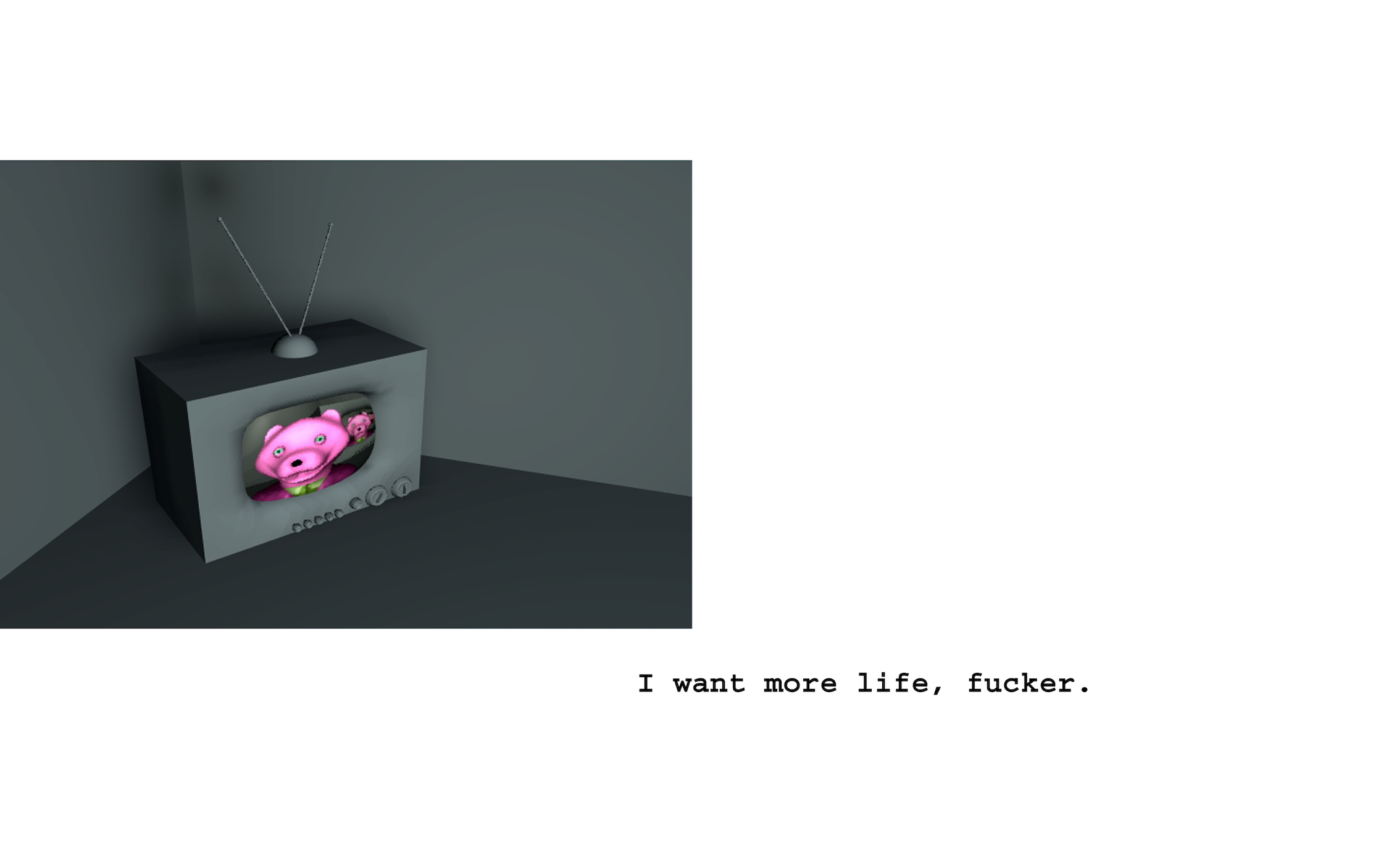

More Life, my animation in the Ordinals auction, featured an avatar that I created in that period. I made a series of six-foot gouache paintings on paper, based on an illustration in Dr. Faustie’s Guide to Real Estate Development. This was my first confrontation with the “not-art” problem. An important New York gallerist sent a collector to my studio. After listening to me explain my paintings and how they used as their source illustrations from one of my books but repainted at a larger scale, the collector pronounced the work “not art” and departed. He intuited that, although the paintings of my Dr. Faustie pages looked like pop art and were made on traditional rag paper mounted on stretched linen using rabbit-skin glue—techniques developed during the Renaissance—they were nevertheless structurally different from it. When Roy Lichtenstein made paintings of comic book pages, he was being playful and naughty, but still acting within the acceptable framework of art. Lichtenstein conceived of comic pages like apples, an element in a contemporary version of a still-life painting.

A few days after the Sotheby’s Ordinal auction closed, February 8, someone unfamiliar sent me an email. He’d just bought a small untitled oil painting I made in 1994, exactly 30 years ago! It featured the same Dr. Faustie pink bear that figured as the avatar in More Life (2000), the 5-second animation I had inscribed as an Ordinal, and which also appeared in my 1996 graphic novel. He asked what the work was about. It was a painting that combined art and text, as all my work from the 1990s did. I thought of mixing the two as a kind of paradox, of pure perception and of analytic thinking., related to another impossible belief that inscribing a tiny file into one millionth of one millionth of a Bitcoin embeds it into infinity. A ritual enactment and an impossible thought, a logical syllogism in which language uses itself to cancel itself. A new alchemy.

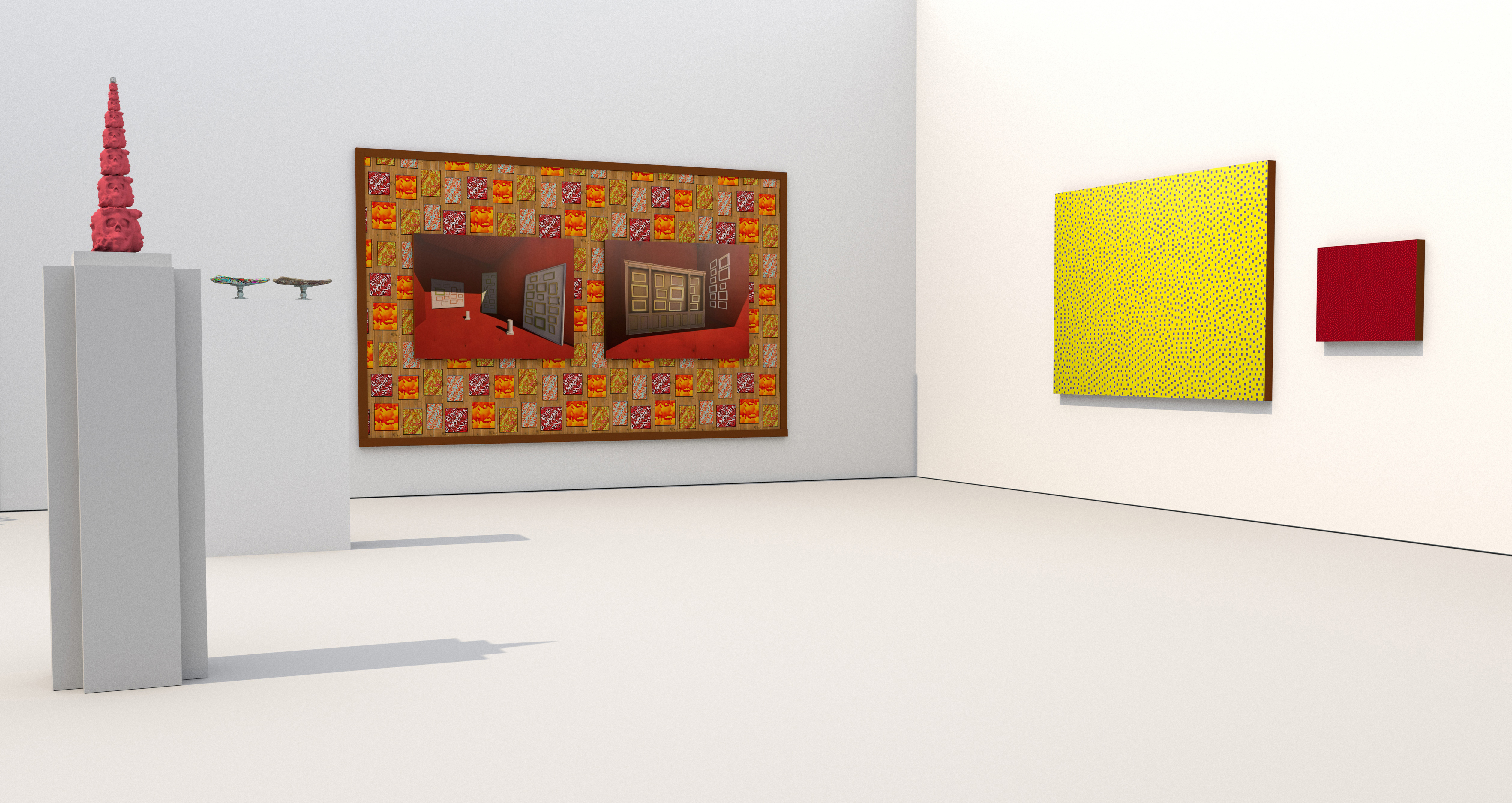

My production process is like my message, a dance of opposites, of opposing forces, generative and destructive. Lately, when I make things, the conflict is embodied by computer-assisted production and the handmade, and by contrasting organic materials and simulated ones. I start with handmade pattern-paintings, tiling culled from monumental buildings plucked from the history of collapsed empires, then hand-painted with a tiny brush. I build on them, layering on top renditions of my still life stage set, built in game space that I then spray on top, using a computer-driven air brush, to be then sanded, repainted and stained. In so doing, I harness opposing forces - of creating and destroying, of making, unmaking and remaking, that then come together in a visually uncanny work - a paradox, hovering in a liminal space somewhere between the real and the not.

My production process is like my message, a dance of opposites, of opposing forces, generative and destructive. Lately, when I make things, the conflict is embodied by computer-assisted production and the handmade, and by contrasting organic materials and simulated ones. I start with handmade pattern-paintings, tiling culled from monumental buildings plucked from the history of collapsed empires, then hand-painted with a tiny brush. I build on them, layering on top renditions of my still life stage set, built in game space that I then spray on top, using a computer-driven air brush, to be then sanded, repainted and stained. In so doing, I harness opposing forces - of creating and destroying, of making, unmaking and remaking, that then come together in a visually uncanny work - a paradox, hovering in a liminal space somewhere between the real and the not.

Similarly there is an idea that the Art Market and Art itself are opposites, that the art market corrupted the Art World, stripping it of profundity. I reject this. The speculative market is a byproduct, resulting from the mythological status of art itself. The Market didn’t destroy art. It is art. Not to say it isn’t dangerous. But good art should be dangerous, should be melancholy and threatening. Art is more gold than money, but gold is not money. Gold is eternal life, and that’s why we want it. Artists typically eschew money. Who needs money if you can make art? If it enters the canon, or the ledger, or is inscribed into the blockchain, eternal life is a done deal. The good thing about Ordinals is that artists can inscribe them into the canon/ledger themselves (for a smallish fee). Perhaps we are worth a lot of money, or perhaps just a little (me), but in the end, it doesn’t really matter. The canon is the tablet, and crypto currencies are certainly both a symptom and a cause of the systems collapse we are now experiencing across many fronts. With Ordinals, the ledger and gold converge into a single canonical thread. So heaven help us

Bibliography

Adam Curtis, Can't Get You Out of My Head: An Emotional History of the Modern World, six-part BBC documentary television series. It was released on BBC iPlayer on 11 February 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hNsoMfuZZqk&list=PL-R20m4MXU6v109QyZ8BKkncR29_OUrWv

Brett Scott, Cloud Money, first published in Vintage, 2023, first published in hardback by The Bodley Head in 2022

Claudia Hart and Claudia Herbst, ‘Virtual Sex: The Female Body in Digital Art’, Bad Subjects, 2005 (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228477156_Virtual_Sex_The_Female_Body_in_Digital_Art)

David F. Noble, The Religion of Technology: The Divinity of Man and the Spirit of Invention, New York: Knopf, 1997

Donna Jo Napoli with illustrations by Christina Balit, A Treasury of Egyptian Mythology: Classic Stories of Gods, Goddesses, Monsters & Mortals, National Geographic, 2013

Ed Regis, Meet the Extropians, Wired, October 1,1994, https://www.wired.com/1994/10/extropians/

Finn Brunton, Digital Cash: The Unknown History of the Anarchists Utopians, and Technologists who created Cryptocurrency, Princeton University Press, 2019

Greg LaBlanc, The Libertarian Roots of Cryptocurrency, featuring Finn Brunton, the unSILOed Podcast with Greg LaBlanc, 2023

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uylh0FEI9No&t=1417s

Jamie Bartlett, The Dark Net: Inside the Digital Underworld, 2015, Melville House, republished in American Scientist, 2015, https://www.americanscientist.org/article/cypherpunks-write-code

Malaclypse the Younger and Omar Khayyam Ravenhurst, Principia Discordia: How I found Goddess And What I Did to Her When I Found Her (The Magnum Opiate of Malaclypse the Younger Wherein is Explained Absolutely Everything Knowing About Absolutely Anything, first published in a limited edition of five copies n 1965; Fifth Edition: Must Have Books, 2022

Neil Gaiman, Norse Mythology, W.W. Norton & Company, 2017

Rachel O’Dwyer, Tokens: The Future of Money in the Age of the Platform, Verso, 2023

Rhea Myers, Proof of Work: Blockchain Provocations, 2011-2021, Urbanomic Media Ltd, published in association with Furtherfield and distributed by the MIT Press, 2022

Suzanne de Brunhoff, Marx on Money, Verso, 2015 (Editions socialism 1973)

Ouutlnds!#?

The Digital Combine

Claudia Hart

June 8, 2022

The metadata field of an NFT’s smart contract offers a new way for artists to suture elements of hybrid works.

In 2020, I imagined myself as a forger, painting copies of famous works by the masters of twentieth-century modernism. My goal was to mint these forgeries, thereby reproducing them as unique digital objects and securing by contract my individual authorial rights. Later that year, I fabricated this series. I invented an elaborate process involving a computer-controlled airbrush machine. First, I built a series of 3D computer models. Then I “painted” them in a software program with a digital brush that simulated watercolors. I arranged the models to create 3D still lifes in virtual reality rooms. Then I rendered out these set-ups as the source files needed to drive my machine. At last the machine and I produced the paintings. They were illusionistic and uncanny, like trompe-l’oeil paintings of the nineteenth century. I exhibited my first forgery with its source file, which was the digital picture I minted. I conceived of these elements as two halves of a mixed-reality whole I called a “digital combine.”

The more I thought about this combine, the more I realized that my true source file was not the digital one I described above, but the story I am currently telling. A digital combine is not a forgery or a version. Rather, it’s a poetic resolution of the mind-body problem: a concept plus a tangible object and the narrative that connects them. Although I coined the term to describe an artwork of my own, I knew it could also be used to describe the work of other artists who also make a certain kind of hybrid artwork, both digital and physical.

I think of NFTs as a kind of magical enactment, an act of prestidigitation—something metaphysical.

A digital combine mixes tangible materials—like paint, wood, or paper—with a file: a jpeg, mp4, mp3, txt, a piece of software, or anything else an artist might imagine. The digital object can be encrypted and stored in the cloud, verified by a smart contract that can include metadata linking the digital and tangible things together. My smart contract, a modification of the standard ERC-721 format, specifies that my digital combines consist of both digital and tangible elements, and that the metadata is also a part of the work. In doing this, I am expanding on the notion that the context of an artwork, including the language used

to define it, is what makes it art.

to define it, is what makes it art.

Smart contracts aren’t really that smart. They’re more like a gentlemen’s agreement than a contract, because they are not enforceable under current laws. Yet they are still quite convincing because of their forceful and obscure style. Both the programming language used to code smart contracts and the legalese of regular contracts are comprehensible only to the initiated. The worlds of coding and of law each constitute a kind of priestly cult, and it is not coincidental that they are designed to uphold markets. Endowed with the power implied by the contract’s hermetic language, NFTs transform liminal things into ordinary, tangible ones. Once encrypted and minted, a digital object becomes nonfungible and unique in the same way that a hand-carved sculpture is. This is a powerful and seductive idea. I think of NFTs as a kind of magical enactment, an act of prestidigitation—something metaphysical.

I borrowed the term “combine” from Robert Rauschenberg, who in the late 1950s strategized an art-historical category based on his own practice. One signature combine is Monogram (1955–59), which consists of a stuffed goat plunged through the center of a rubber inner tube, then glued upright to a wooden plank roughly painted with crude brush strokes and pasted with elements of paper collage. Monogram is monstrous, an impossible object, coming into existence as an artistic concept when Rauschenberg granted it status by naming it. A combine transforms a weird, implausible thing into a knowable—albeit very odd—one. I did the same for my own hybrids.

To expand my taxonomy, I curated two exhibitions under the “Digital Combines” title, at Honor Fraser Gallery in Los Angeles and Bitforms in San Francisco, featuring artists working with mixed-reality painting, augmented-reality sculpture, and other hybrid forms. Each work is installed as a physical piece, with an associated QR code placed on the wall nearby, in a position where you’d find a wall label in a museum; this is the portal to the cloud, where the work’s digital element resides. Daniel Temkin was in both shows. His optical yellow Floyd-Steinberg, 16.4% Lavender (2020) unites a painting with an animated gif. To make the animation, Temkin starts with a solid color and then applies a dithering algorithm, which is normally used to simulate shading in digital photography. He then paints the resulting field, now filled with colored rectangles—a process he has dubbed “hand-rendering.” Temkin chooses a complementary color for his rectangles, which triggers the eye to hallucinate a flickering after-effect. With this gesture, he unites human perception with procedures of pure logic to create an optical glitch, a phenomenon seen by the mind alone.

A combine transforms a weird, implausible thing into a knowable—albeit very odd—one.

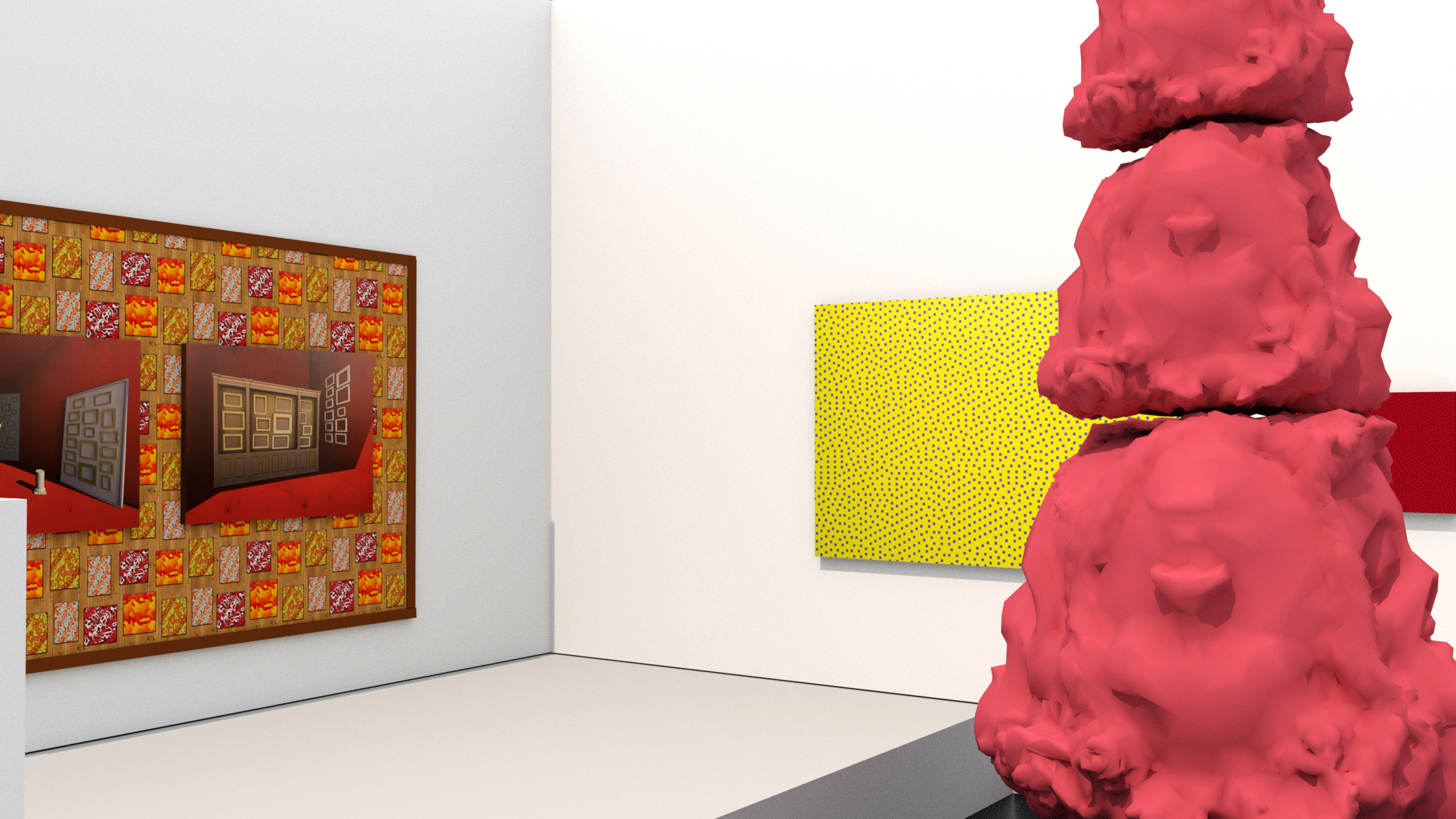

Auriea Harvey’s sculpture The Mystery v5 (tower), 2021, is a stack of grotesque gargoyles that evokes the Tower of Babel. Harvey begins her process by creating a 3D model, from which many works are then made. The Mystery v5 (tower) and its digital component, The Mystery v5-dv3 (axis mundi), use the same mask-like form, a remix of scans of the artist’s own face. Colored clay and pigment act as decorative embellishments to the tangible sculpture. This work is meant to be experienced interactively, not only by looking at it from various angles in the physical world, but also from within a wallet, on a touch screen, or in augmented reality, where a user may tumble the virtual version to access different views.

Repairs (2020–21) by Will Pappenheimer is a trickster installation, combining a physical assemblage with a custom augmented-reality app, loaded onto an Apple tablet with his NFT, a text file giving a bare-bones verbal description of the scene. Repairs belongs to a series of domestic tableaux constructed from readymade items that double as both still-life and stage set for a 3D animated scene. The objects—which include “a flat earther anti-science conspiracy melted earth ball” and “a small tunnel box guarded on both ends by wrathful deities from India”—are selected to evoke the social conflict that intensified following the 2016 US presidential election. In the animation, a CGI therapist speaks in a calming voice. Pappenheimer merges physical and digital components to create a site for meditation, with the intent of healing a polarizing political divide.

![Reference image for Claudia Hart’s Hermitage 1.0, 2021]()

Like Pappenheimer’s work, mine is a stage set, juxtaposing poetic, metaphoric objects. In my case these are works of art. Hermitage 1.0 (2021) is a trompe-l’oeil still life with dozens of empty wooden frames. It is inspired by a photograph of the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad, taken during World War II when paintings were stripped from their frames and hidden in the countryside to prevent their pillage. Hermitage 1.0 hangs on augmented-reality wallpaper, made to be viewed through my custom Combines app, produced for this work. It is covered by a faux-wood motif, which together with small abstract paintings, provide trackable codes linked to flickering gifs of mottos inspired by Sun Tzu’s ancient Chinese military treatise The Art of War. The QR code mounted on the wall beside the tangible work links to a variant of the text you are currently reading: my “mintable.” The code links the viewer’s immediate physical surroundings to the cloud, which I think of as an agnostic version of heaven representing the ephemeral, metaphysical space of mind. It is also another associated symbol that—like markets, legal language, and the mathematical coding—endows NFTs with their magical cultural power. The specificity with which the NFT connects and defines these contexts marks a radical ontological shift, creating a new way of seeing what constitutes an object.