The Armory Women (2024)

Nine computer-assisted paintings, sizes variable

Acrylic gouache paint, graphite, colored pencil, pure pigment

submerged in plastic resin.

The Armory Women project reimagines seven little-known painters selected from the 120 women artists exhibited at the International Exhibition of Modern Art that was organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors in 1914. At the 2024 Armory Art Fair, Claudia Hart created a group of nine paintings,The Armory Women, in response, part of a fair section curated by Robyn Farrell, in the booth of Montreal gallery Patrick Mikhail. To do this, Hart invented a new way to paint. Hart’s pictures combine classical brush painting with the advanced simulation technologies normally used in scientific visualizations and 3D game environments.

These paintings remix post-Impressionist and Fauve paintings by Marion H. Beckett, Marie Bracquemond, Emilie Charmy, Marjorie Organ Henri, Marie Laurencin, Jacqueline Marvel, and Katharine Rhoades, with Hart’s very contemporary versions of them. Hart chose these women because she felt that they were particularly gifted: her “geniuses.” What she then discovered when she studied them was that many were founding members of the Fauvist movement, active and celebrated in their day. Later, when the art market became powerful, they were systematically erased from history.

When the prices of Matisse and Derrain went to the multi-millions, the original Armory Women paintings could be purchased at small auction houses for a few thousand. They had been successfully removed from the art canon! Hart’s Armory Women project was an attempt to reinsert them. To do this, she invented a novel technique mixing a sophisticated computer-assisted UV printer with a variety of stylistic handpainting. UV printer technology is exactly like that of a CNC router, but spraying pigment instead of cutting, and allows an artist to accomplish what was previously impossible. Hart was able to produce, what she calls, “ghost paintings.” Her novel process is a kind of dance between the hand-made and the computer-assisted, channeling the ghosts of the past in order to re-present art history, inserting the voices of forgotten women.

Jacqueline Marval was born in 1866 near Grenoble. She was known then as Marie-Josephine Vallet, and grew up to become a married school teacher and a mother. After the death of her child, her marriage failed, and at the age of 29, she fled to Paris, to become a seamstress specializing in spectacularly embroidered clothing, self taught, for which she was celebrated. In Paris she met painters, living in the artists’ quarter Montparnasse. There she met Henri Matisse and George Rouault, to then join them at the Ecole de Beaux Arts in the class of Gustave Moreau - the famous Symbolist painter. At that time, male painters could be subsidized by the state, but women were forbidden. So Marie-Josephine paid for private tutoring there, which was permissible, with her embroidery earnings.

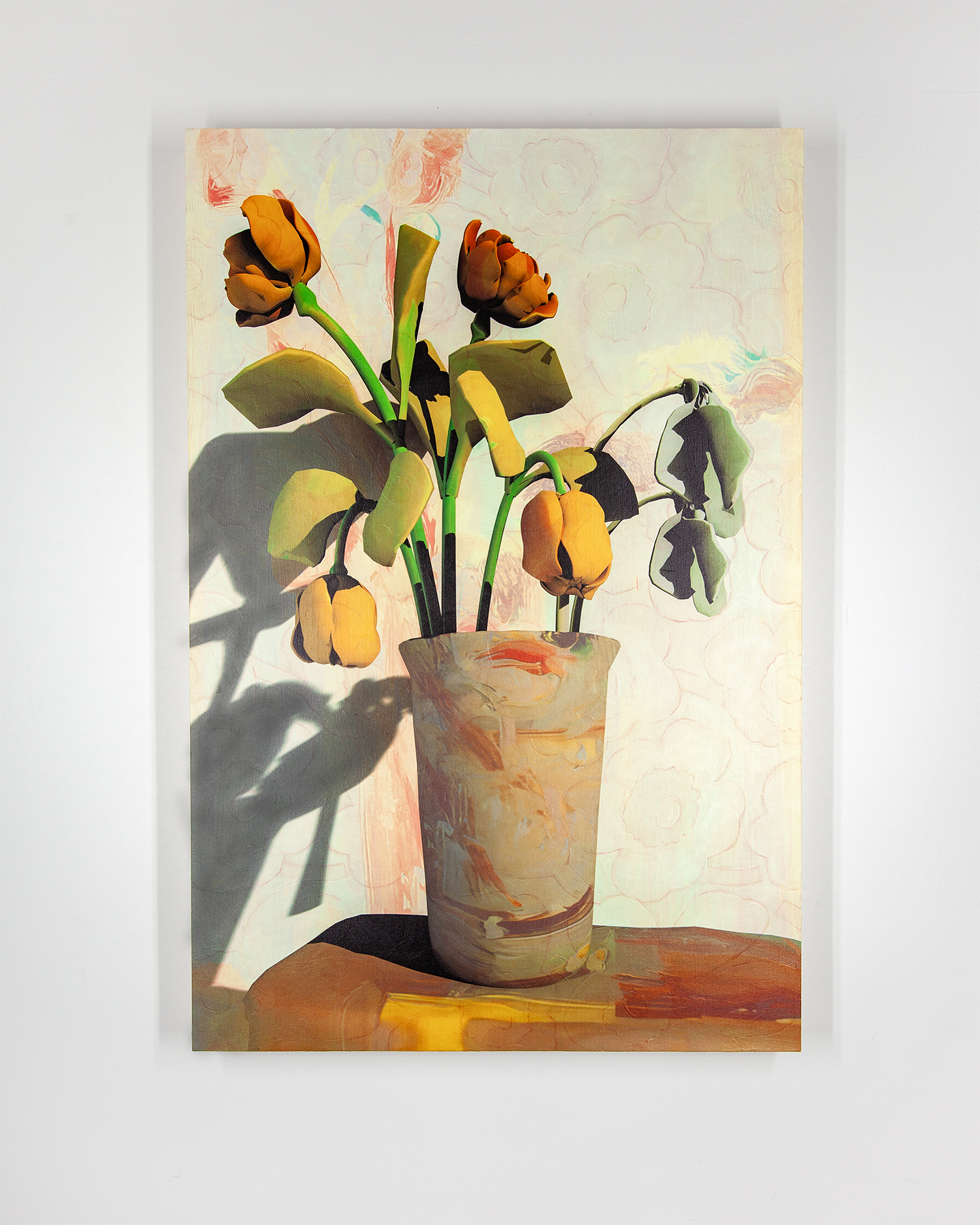

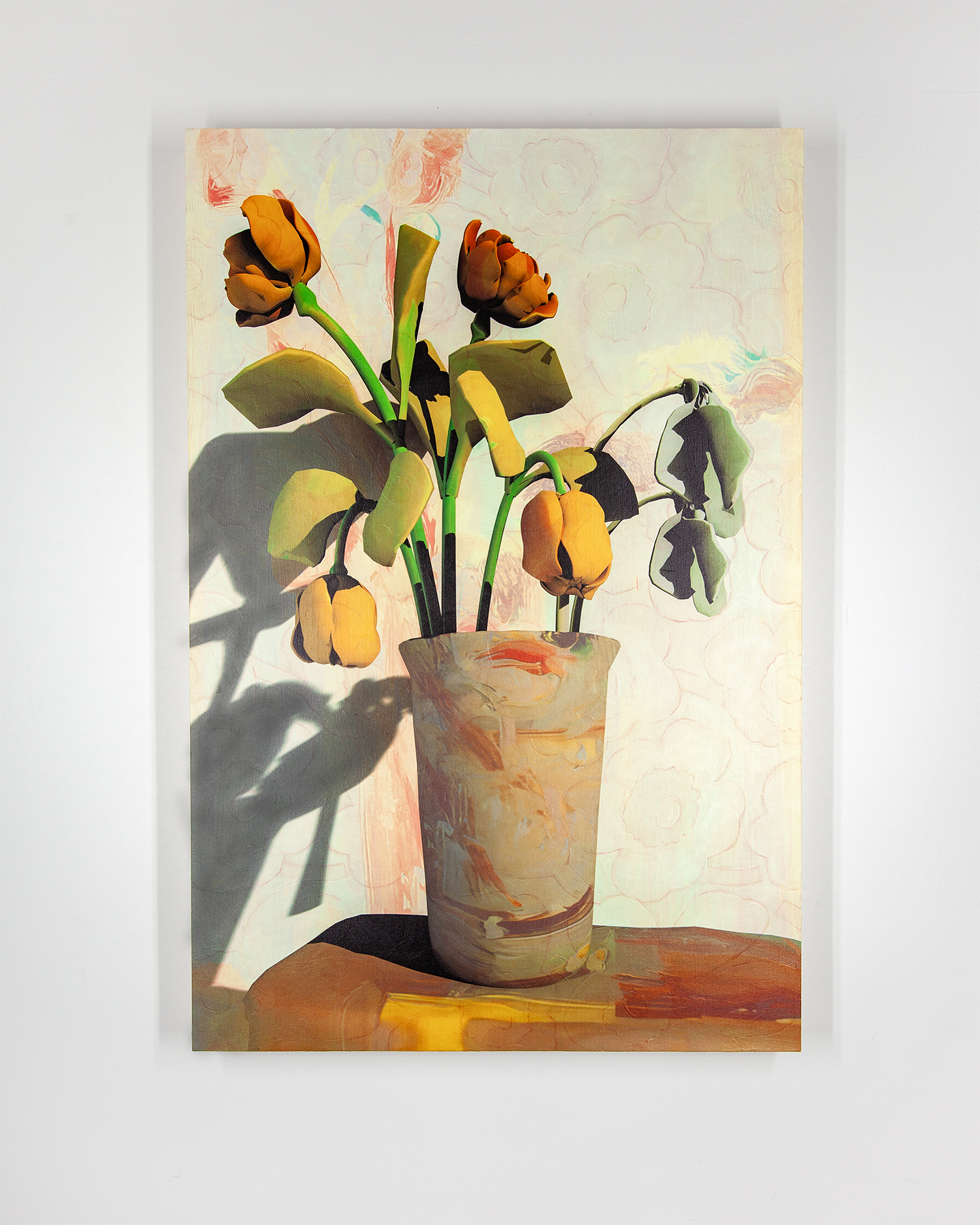

As a painter, Valet changed her identity and her personal style, transforming into Jaqueline Marval. The class of Moreau broke from him, choosing color over representation, embracing instead a wild colorful style. They were called Fauves - The Wild Beasts. Jacqueline was the only woman; in my mind, she was a peer of Matisse,with a talent far beyond that of Andre Derain, another well-known painter from the group. In 1901, Marval submitted nine of her nudes to the Salon des Independent, established 15 years early by Cezannne, Toulouse-Lautrec and Pissaro. All were all accepted. Marval was the first woman painter of seductive nudes, and even more significantly, the first woman nude self-portraitist, staring brazenly into the eyes of her viewers. Ambrose Vuillard, a celebrated gallerist of that era, bought all of them, to then re-sell all of them. At the same time, Berthe Weill, the first and only woman gallerist in early 20th-century Paris, exhibited Maval, along with Suzanne Valedon, another celebrated woman painter who began her Ecole training as nude model, one of the only ways a woman could enter a Beaux Arts class without payment. Weill also showed and sold the first paintings of Matisse and Picasso. Towards the end of her life, Marval fell into poverty.She died of cancer at the Hôpital Bichât, a public hospital in Paris, in 1932. In 2022, this painting, her Roses in a Vase was sold at Auction for $3,500.

The most recent auction prices for Matisse were close to $81 million. The Fauvist painter, Andre Derain, now sells for $25 million. In 2023, Marval’s Roses in a Vase was again put up for auction with an evaluation price of $3,850 to $5000 along with this painting, her Flowers, from the same period. Neither sold.

Émilie Charmy was the granddaughter of the bishop of Lyon, born Émilie Espérance Barret in 1878 into a bourgeoisie family in Saint-Etienne, France. She was orphaned at age 15, and therefore educated at a private Catholic school to become a teacher, her education including “cultural” refinement - meaning playing the piano and the production of floral paintings. Émilie had larger ambitions. She adopted the pseudonym Charmy and began a serious training in art in the studio of Jacques Martin in Lyon, where she was introduced to the work of the Post-Impressionists. Her goals briadened, so in 1902 she fled for Paris and Montaparnasse where she met Jacqueline Marvel, Matisse and the other Fauves. Like Marvel, she was invited to participate in the Impressionist’s Salon d'Automne in 1905. Charmy also caught the attention of the art dealer Berthe Weill, who also supported both Marie Laurencin and Suzanne Valedon. These were women breaking from traditional notions of gender - what was then the femme-peintre - signaling a radical expansion in the visibility of female artists.

What made Charmy’s art distinctive and provocative in its own time was that it seemed to elude simple gendered expectations. The critics were unanimous in finding virile qualities in her expressive, rough and physical style, as well as in her subjects - erotic nudes - paintings of her friends and peers. The French novelist Roland Dorgelès described Charmy as "a great free painter; beyond influences and without method, she creates her own separate kingdom where the flights of her sensibility rule alone." Here work tends towards abstract and I think of it as foreshadowing Abstract Expressionism. To me, Charmy was forty years before her time. The most famous quote about her also came from Dorgelès, “Émilie Charmy, it would appear, sees like a woman and paints like a man.” Although meant as a compliment, his remark is naively demeaning but nevertheless indicates that Dorgeles intuited Charmy's resistance to traditional gender roles, making her extraordinary for her time - hybrid, a post-human Cyborg - a woman of the future. Interestingly, Dorgelès was the recipient of the Prix Femina, a French literary prize awarded each year by an exclusively female jury. The prize, established in 1904, was awarded to both male or female writers, until it was abandoned in the 1950s. Sadly, however, the effects of this were limited - like all of her femme-peintre peers, and unlike the Modernist patriarchs Picasso, Matisse, Cezannae, et. al - Charmy never achieved market status, so she fell out of the public eye after the Second World War, continuing to paint into the 1970s. She died in Paris In 1974 at the age of 96.

I studied art history at NYU in the mid 1970s. At that time, I learned about Marie Laurencin, but had no idea she was an artist. I thought her sole accomplishment was as being the “muse” and lover of Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet, playwright, short-story writer, novelist, art critic, and a powerful figure in Paris during the first decades of the 20th century. This is what I was taught, but I was taught wrong!

Last year, from October 22, 2023 – January 21, 2024, the Barnes Foundation, with its major collection of French Impression, staged a show with her: Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris. As the New York Times review described it: “This show emphasizes Laurencin’s vision of a sapphic world without men, which makes it the first of its kind in a major institution.”

In Paris, in her twenties, Laurencin was also a part of the femme-peintre group that included Suzanne Valedon, Emilie Charmy, and Jacqueline Marval, supported by the art dealer Berthe Weill. Like Charmy, Laurencin practiced an intentionally naive pictorialism that took its cues from the Fauves, but favored pastels and the color pink. Both made erotic nudes of their friends and decorative flower paintings.

Art Net is my source for tracking the auction and market value of The Armory Women and it is market value that actually determines how The Armory Women fare in art history. It explains who we know and who we don’t.

In her thirties, Marie married a German bisexual Baron, moving with him to Spain during World War I. In Madrid and Barcelona, she socialized with Diego Rivera and collaborated with Francis Picabia on his Dadaist magazine, 391.

Back in Paris and newly single in the 1920s, Laurencin spent her 40s winning critical and financial acclaim. She adopted her lover, Suzanne Moreau-Laurencin, to assure that Suzanne could inherit her fortune. Among her collectors were Albert Barnes, whose foundation produced her 2023 retrospective.

In the 1930s, she was awarded the Legion of Honor, France’s highest national decoration.Three decades after her death, in 1956, the Japanese collector Masahiro Takano established the Marie Laurencin Museum in Nagano-Ken, Japan, the first institution dedicated to a female artist in Japan. In 1989, Takano paid $1.4 million one of her paintings at Sotheby’s, making Laurencin the third-most-expensive female artist at auction that year following Mary Cassatt and Georgia O’Keeffe. Laurencin’s artworks generated $29.3 million at auction over two years in 1989 and 1990, with the average lot price of $84,100, according to Artnet Price Database.

In the 1990s, the stock market crashed repeatedly. Laurencin’s prices depreciated along with the entire Impressionist and Modern art markets. A decade later, her average lot went for $9,500, with $1.6 million in total sales annually. Laurencin’s prices never fully recovered, but her historical legacy is assured.

I love this still life by Marie Bracquemond. I think of it as a Baroque version of Impressionism, more sensual and physical and dark - Monet meets Caravaggio (I’m thinking of his 16th century Bacchus!). Her story is perhaps typical to women painters of her era. In 1859, she was accepted into the studio of the canonical Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Along with the skills she learned, she encountered problems that followed her throughout her life, later writing that she feared Ingre and that he treated his female students differently than his male. She wrote: "The severity of Monsieur Ingres frightened me...because he doubted the courage and perseverance of a woman in the field of painting... He would assign to them only the painting of flowers, of fruits, of still lifes, portraits and genre scenes." That quote and much of what we know about Bracquemond comes from a biography written by her son Pierre about his parents, Felix and Marie. Felix ran a successful print studio working with Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and Paul Gauguin. According to Pierre, the domineering Felix resented Marie’s career and loathed her Impressionist style, playing an active role in isolating her from the Impressionist movement. She withdrew from public life, and spent most of her time alone, painting in her garden. Despite being referred to as one of “the three great ladies” of Impressionism by Henri Focillon, one of the celebrated French art historians of the early 20th century, the work of Marie Bracquemond to this day remains obscure.

While I don’t think she was as gifted a painter as the rest in my collection of Armory Women, Marjorie Organ Henri (1836-1930) is one of my favorite characters in it (along with Marie Laurencin). I think this is because she was spirited, a force of nature and also very funny!

Marjorie Organ was born in Ireland, the daughter of a wallpaper designer. Her family moved to New York in 1895, where she studied at Dan McCarthy's National School of Caricature. In 1902, at the age of 16, she joined the staff of the New York Evening Journal, where she worked as an illustrator and a cartoonist. There she created "Little Reggie and the Heavenly Twins", my about a foolish man manipulated and teased by a pair of beautiful girls; "The Wrangle Sisters", about best girlfriends and socialites, "Strange What a Difference a Mere Man Makes!", "Girls Will Be Girls", "The Man Haters' Club" and "Lady Bountiful".

In 1908, when she was a student of the New York School of Art, she met its director, the widowed painter Robert Henri, who was one of the leaders of the AshCan School, the New York equivalent Fauvism - taking place at the same time but very different. Ashcan artists painted the working classes, and their paintings were dark and rough. Three weeks later, the two married and Marjorie’s life as a raucous cartoonist ended, instead she painted, exhibiting at the Armory Show in New York City, the Society of Independent Artists (1919-24, 26-28), the McDowell Club (1917-18), the New York Society of Women Artists (1927, 1932), the Morton Gallery (1928) and others, and also managed her husband's business and social life. Henri died in 1929, and Marjorie, although 15 years younger, died the following year.

Katharine Nash Rhoades is another Armory Woman very little known today, although this painting, Larkspur, is in the prestigious Phillips Collection of Modern and contemporary art, acquired in 1964. This work, and another purchased at the same time, are the only remaining paintings of Rhoades early Modern works.The rest she destroyed shortly before her death in 1965.

Most of what I know about Rhoades comes from an impressive feminist history of the period, Modernism and the Feminine Voice: O’Keeffe and the Women of the Stieglitz Circle (2007), by Kathleen Pyne. When Roades destroyed her art works in 1964, she also destroyed all of her letters to Alfred Stieglitz because of their apparently traumatic history. Stieglitz was an early street photographer whose journal and 291 gallery were the cultural centers of early twentieth-century Greenwich Village in New York. Katharine Nash Rhoades and her friend Marion Beckett became part of the Stieglitz circle at 291 in 1911. At that time, the experimental art world was influenced by the theories of sexologists Ellis and Ellen Key, Sigmund Freud, and Henri Bergson - who believed that processes of immediate experience and intuition were more important than abstract rationalism and science for understanding reality. Part of this creed was a belief that women’s essential nature was more like a child’s than that of a man, making women a source of primal creativity.

Katharine and Marion were eager to join the 291 circle and be taken seriously as artists. They needed the mentorship of Steiglitz to do this. Steiglitz pursued Rhoades relentlessly to become and to publicly share their erotic life with the 291 community. Rhoades, not wanting to suffer the social consequences that would befall her at the age of 27 (but not the 48-year-old Steiglitz), refused him. Nevertheless, Rhoades continued to entertain Stieglitz in intimate studio visits, writing him scores of personal letters and poetry in the course of their five-year relationship, that she ultimately destroyed before her death. Steiglitz hung an exhibition of Katharine’s and her friend Marion H. Beckett’s paintings at the 291 gallery in 2015. I couldn’t find any documentation of it in the 291 magazine of that period - aside from one abstract drawing by Rhoades. Steiglitz continued to pressure Rhoades until 1917, when Georgia O’Keeffe arrived on the scene and Stieglitz found his perfect muse. In her later life, Roades became an arts manager, establishing art libraries in New York and at the Smithsonian in Washington DC.

This still life by Beckett is clearly masterful, a beautiful example of Post Impressionism that reminds me a bit of a Van gogh. Marion Beckett was known as a portrait painter. Like her best friend Katharine Nash Rhoades, she was a member of Alfred Stieglitz’s circle in New York, and like Rhoades, did not benefit personally from that culture. In my mind, quite the opposite. Marion, Katharine Rhoades and Agnes Ernst Meyer were known as the "Three Graces" of the 291 scene. Agnes Ernst Meyer described Marion as one of "the most beautiful young women that ever walked this earth", although shy and reserved.

Beckett’s portrait of Mrs. Eduard J. Steichen was exhibited in the 1913 Armory Show. In 1915, Beckett and Rhodes had a joint exhibition at Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery, with no documentation surviving. In 1917, Beckett presented another show, also of portraits, at Marius de Zayas's Modern Gallery.. Among the works presented were portraits of Alfred Stieglitz, Eugene Meyer and Georgia O'Keeffe, used to illustrate a Vanity Fair article in 1922 and a New York Sun article about O'Keeffe's work in 1923. In 1925, Marion exhibited in New York at Montross Gallery.

In 1926, Marion Beckett quit painting, adopted two daughters, and with her sister Estelle, ran the Beckett Water Supply Company until she died in 1949. Fifteen of her paintings were stored by family members until 1997, including the portraits of O'Keeffe and Agnes Meyer. There is no record of these works having been sold.The Georgia O’Keeffe portrait is currently a stock image in the public domain.